أمريكي يعيش في مدينة واشنطن، وهو المدير التنفيذي لمعهد أسبن، والرئيس السابق لشركة سي إن إن الإخبارية، ورئيس تحرير مجلة تايم. وهو مؤلف كتاب ستيڤ جوبز، وكتاب "انشتاين: حياته و الكون"، وكتاب "بنامين فرانكلين: الحياة الأمريكية".

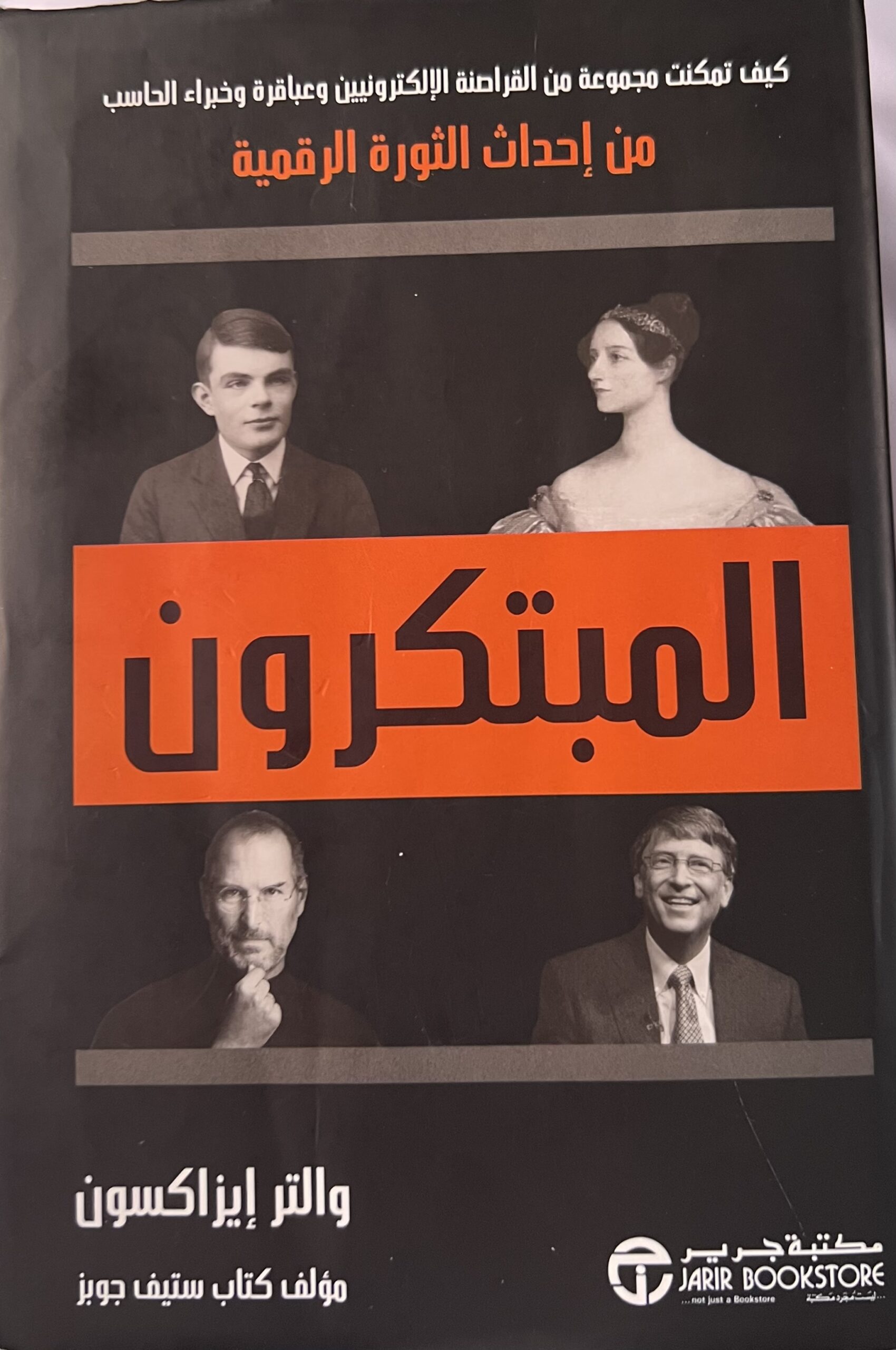

"المبتكرون - كيف تمكنت مجموعة من القراصنة الإلكترونيين وعباقرة وخبراء الحاسب من إحداث الثورة الرقمية" هو كتاب كبير يقع في587 صفحة من تأليف الكاتب الأمريكي والتر إيزاكسون Walter Isaacson عام 2014 ، وهذه هي ترجمة عربية لطبعة اللغة الإنجليزية أعيدت طبعتها عام 2019.

الكتاب يحتوي على مقدمة، و ١٢ فصلاً، ثم الفصول الختامية. وفيما يلي فصول الكتاب الأساسية:

- أدّا ، كونتيسة لافليس

- الحاسب الآلي

- البرمجة

- الترانزيستور

- الميكروتشيب (الدائرة المتكاملة)

- ألعاب الفيديو

- الإنترنت

- الكمبيوتر الشخصي

- برمجة الحاسب الآلي

- على الإنترنت

- الويب

- أدّا لافليس للأبد

الكتاب يتحدث عن قصص الأشخاص الذين كان لهم الدور الأبرز في إحداث الثورة الرقمية التي يشهدها عالم اليوم، ابتداء من أدّا لافليس ابنة اللورد بايرون (رائدة برمجة الحاسب في أربعينات القرن التاسع عشر)، مروراً بالمبتكرين اللامعين من أمثال فانيفار بوش (الذي أوصى باستخدام جهاز التحليل التفاضلي وهو حاسب آلي تناظري كهروميكانيكي عام 1931، ثم نشر مقاله As We May Think واصفا فيه الحاسب الشخصي عام 1945)، آلان تورينج (الذي وصف في ملاحظاته العلمية التي يصف فيها حاسباً آلياً عالميا عام 1937، كما عمل على فك الشفرة الألمانية سنة 1939، ونشر مقالا في 1950 يصف فيه الذكاء الاصطناعي، وقد انتحر عام 1954)، جون فون نيومان (عالم رياضيات مجري الأصل، والذي عمل على الحاسب إينياك ENIAC عام 1944 ثم كتب المسودة الأولى حول حاسب إدفاك EDVAC عام1945)، جيه سي آر ليكلايدر (والذي نشر مقاله عن تعايش الإنسان والحاسب الآلي عام 1960، واقترح في عام 1963 إنشاء شبكة حاسوبية عالمية)، دوج إنجيلبرت (صاحب البحث المشهور عن "زيادة الذكاء البشري" والذي نشره في 1962، واخترع هو و زميله بيل انجليش "فأرة الحاسوب" سنة 1963)، روبرت نويس (الذي اخترع هو ورفاقه المعالج الدقيق بشكل مستقل عام 1959)، بيل جيتس(مؤسس شركة مايكروسوفت عام 1975، والذي كتب في ذات العام هو و زميله بول ألان "لغة بيسك" من أجل حاسب Altair)، ستيف جوبز(مؤسس شركة أبل)، ستيف ووزنياك (والذي عمل مع ستيف جوبز في إطلاق الحاسب أبل-١ عام 1975، والحاسب أبل-٢ سنة 1977)، تيم بيرنرز-لي (والذي أعلن في 1991 عن إنشاء "الشبكة العنكبوتية العالمية")، لاري بيدج و سيرجي برين (اللذان أنشئا شركة جوجلعام 1998)، وغيرهم الكثير مما لا يتسع المجال لذكرهم جميعاً.

كما يتطرق الكتاب عن كيفية حدوث الابتكار والإبداع والاختراع، وكيف يؤدي التعاون والعمل الجماعي إلى هذا القدر من الإبداع العالمي.

وبعد رحلة شائقة في فصول الكتاب الـ11 الأولى عن قصص المبتكرين وسِيَرِ الأعلام الرقميين، تحدث الفصل الثاني العشر وهو الفصل الأخير عن أهم الدروس المستفادة من قصة الابتكارات التي صنعت العصر الرقمي، نلخص أهمها بإيجار كما يلي:

- الإبداع عملية تعاونية، وأن الابتكار يأتي في الغالب من خلال فرق لا من خلال تجليات عباقرة منفردين.

- قد يبدو العصر الرقمي ثورة، لكنه اعتمد على توسيع حجم معارف انتقلت إلى جيل من جيل سبق، لم يكن التعاون قائما بين معاصرين فقط، بل كان قائما بين أجيال متعاقبة، وأفضل الفرق انتاجا هي تلك التي جمعت مجموعة واسعة من التخصصات المختلفة.

- على الرغم من أن الإنترنت قد وفر أداة لأشكال تعاونية افتراضية وعن بُعد، إلا أن إبداع العصر الرقمي قدم درسا آخر وهو أن الاقتراب المادي بين المبتكرين مفيد (مثلما حصل في معامل بيل لابس)

- لأن الإنسان اجتماعي بطبعه، فإن كل أداة رقمية، بقصد أو دون قصد، صادرها البشر لغرض اجتماعي: لتكوين مجتمعات، لتسهيل تواصل، للتعاون في مشروعات، وتمكين شبكات التواصل الاجتماعي.

- تكافل البشر مع الآلات يمكِّن البشر من إضافة عنصر واحد أساسي لهذه الشراكة: الإبداع. وهذا الإبداع سيكون "وليد أناس قادرين على الربط بين الجمال والهندسة، بين الإنسانية والتكنولوجيا، بين الشعر والمشغلات الآلية.." ص521.

ومن جملة الدروس التي استنبطها المؤلف في الفصل الثاني [ص 92] بعد حديثه عن ولادة الحاسبات، هو أن "الإبداع عادةً ما يكون نتيجة جهد جماعي، يتضمن التعاون بين أصحاب الرؤى والمهندسين، وأن الإبداع يأتي من الاعتماد على مصادر متعددة، ولا تأتي الابتكارات مثل الصاعقة أو مثل مصباح مضيء يخرج من رأي الفرد المنعزل في قبو أو في علية المنزل أو في مرآب، إلا في كتب الحكايات القصيرة فقط."

ثم عزز المؤلف تأكيد هذا الدرس الأخير الهام في أكثر من موضع من كتابه بصياغات متنوعة، على نحو قوله في الفصل السابع (الإنترنت) [ص259]: "إن عجلة الابتكار تسير بفضل جهود الأفراد الذين يضعون نظريات جيدة ويحصلون على فرصة العمل ضمن فريق يستطيع تنفيذ تلك النظريات".

ولقد وصف الكاتب الابداع الرقمي - والطرق التي أدت إلى ظهوره وازدهاره - في الفصل الأخير [ص 501] حين قال: "ظهرت تلك الآلات بالفعل في الخمسينات من القرن العشرين، وخلال ثلاثين عاماً تلت ذلك، خرج للعالم ابتكاران تاريخيان أحدثا ثورة في حياتنا، الرقائق الدقيقة التيمكنت من إنتاج حواسب أصغر حجما جعلت منها أجهزة منزلية، وشبكات تحويل الطرود التي سمحت بهذه الأجهزة بأن تتصل ببعضها كعقد في شبكة. ظهور الحاسب الآلي والإنترنت سمحا بالإبداع الرقمي، وتبادل المحتويات، وتكوين المجتمعات، وشبكات التواصل الاجتماعي بالازدهار على نطاق هائل، لقد حققت تلك الطفرة ما أسمته أدّا "العلم الإبداعي"، الذي ارتبط فيه الإبداع بالتكنولوجيا ارتباطا لا ينفصم بشكل يشبه نول جاكارد."

وأثبت الكاتب من خلال الأمثلة الواقعية من قصص المبتكرين بأن هناك ثلاث طرق تتشكل بها الفرق في العصر الرقمي:

- إما من خلال تمويل وتنسيق حكومي (وهذه بنت الحواسب الأولى و أوائل الشبكات، وكان ذلك بالتعاون مع جامعات وشركات مقاولة خاصة كجزء من مثلث حكومي أكاديمي صناعي).

- أو من خلال المشروعات الخاصة (وحدث هذا في المراكز البحثية للشركات الكبرى مثل معامل بيل لابس، وزيروباركس، أو عبر شركات مغامرة جديدة مثل تكساس انسترومنتس، إنتل، أتاري، جوجل، مايكروسوفت، آبل) وكان الباعث الحقيقي هو تحقيق الأرباح لمكافأة مبدعيهم وكذلك لجذب الاستثمارات.

- أو عبر عمل عام تطوعي عن طريق أقران يتبادلون أفكارهم مجانا و يقدمون إسهاماتهم دون إشراف حكومي أو تحت مشروع خاص مباشر (وكثير من التطورات التي صنعت الانترنت وخدماته وقعت بهذه الطريقة، مثل موسوعة ويكيبديا ومتصفح ويب)

"- اقتباس من الفصل الثاني [ص 78]: قال إيكرت "عالم الفيزياء هو شخص يهتم باكتشاف الحقيقة، بينما يهتم المهندس بتنفيذ المهمة المطلوبة"."

"- اقتباس من الفصل الثاني [ص 87]: تعريف ويكيبديا 2014 للحاسب الآلي هو "جهاز متعدد الأغراض يمكن برمجته بهدف تنفيذ مجموعة من العمليات الحسابية أو المنطقية بشكل آلي"."

"- اقتباس من الفصل الثالث [ص 102]: “ساعد الطاقم هوبر على انتشار المصطلح bug (خطأ فني) و debugging (تشخيص الأخطاء وعلاجها). كانت نسخة مارك ٢ مبنية داخل مبنى بدون نوافذ، وفي إحدى الليالي تعطلت الآلة وبدأ الطاقم البحث عن المشكلة، ولقد وجدوا فراشة يبلغ طول جناحيها أربع بوصات وقد انسحقت داخل أحد المرحلات الكهروميكانيكية. وقام الطاقم باستخراج الفراشة، ومنذ ذلك الوقت أصبح الطاقم يشير إلى البحث عن الأخطاء بـ debugging the machine "

"- اقتباس من الفصل الخامس [ص 205]: كان شعار "آندي جروف" أثناء عمله في شركة انتل "النجاح يورث الرضا. والرضا يورث الفشل. المرتاب فقط هو من ينجو"."

"اقتباس من الفصل السابع [ص 237]: نشر جيه سي آر ليكلايدر بحثه عن تعايش الإنسان والحاسب الآلي Man-Computer Symbiosis عام 1960 وقال فيه "أرجو في المستقبل القريب أن تعمل العقول البشرية والآلات الحاسوبية معاً بشكل وثيق للغاية، وأرجو أن تؤدي الشراكة الناتجة إلى التفكير بطريقة لم يفعلها عقل بشري من قبل، وإلى معالجة البيانات بطريقة لم تفعلها آلات التعامل مع البيانات التي نعرفها في الوقت الحالي"، وهذه العبارة أصبحت أحد المفاهيم الأساسية في العصر الرقمي. "

"- اقتباس من الفصل السابع [ص 259]: "إن معظم مبتكري شبكة الانترنت فضلوا نظاماً ما يقوم على توزيع الفضل والتقدير توزيعا كاملًا .. لقد ولدت شبكة الانترنت كروح للتعاون الجماعي وتوزع اتخاذ القرار، وكان مؤسسو الشبكة يحبون حماية هذا الميراث؛ ولقد أصبح هذا طبعا أصيلاً في شخصياتهم، وفي الحمض النووي لشبكة الانترنت نفسها"."

"- اقتباس من الفصل التاسع [ص 390]: "من هنا يمكننا القول إن الإبداع لا يأتي من قبل المبتكرين، ولكن من قبل الأشخاص الذي يستطيعون توظيف هذه الابتكارات بشكل جيد"."

"- اقتباس من الفصل العاشر [ص 428]: تماماً مثل ستيف جوبز حين سمى شركته آبل، بأن من المهم أن يكون الاسم "بسيطا، وغير عدائي، وربما ساذجا إلى حدٍّ ما"."

"- اقتباس من الفصل الحادي عشر [ص 458]: في عام 1997 قام جون بارجر- الذي صمم الموقع الساخر روبوت ويزدوم - بصياغة المصطلح weblog، وبعد ذلك بعامين قام مصمم الويب، بيتر ميرولز، بتقسيم المصطلح على سبيل المزاح إلى جزأين، لكي يصبح We blog. ذاع صيت blog، لدرجة أنه بحلول عام 2014 كان هناك أكثر من 874 مليون مدونة "بلوج" في العالم. الجدير بالذكر بأن كلمة blog أدرجت في قاموس أكسفورد للغة الإنجليزية كاسم وفعل في مارس 2003. "

"- اقتباس من الفصل الحادي عشر [ص 493]: أضاف قاموس أكسفورد للغة الإنجليزية كلمة google كفعل بمعنى "يبحث في موقع جوجل" عام 2006."

"- اقتباس من الفصل الحادي عشر [ص 494]: ظهر شخص آخر يحمل مشروعا مشابها لمشروع بيج رانك (للثنائي لاري بيدج و سيرجي برين - مخترعا محرك البحث جوجل)، كان هذا الشخص مهندس صيني يُدعى يانهونج (روبين) لي، والذي أسس موقع بايدو Baidu الذي أصبح أكبر محرك بحث في الصين ومنافسا عالميا قويا لجوجل."

كتاب دسم يعطي نبذة كافية عن أهم قصص نجاح المبتكرين وعباقرة الحاسب وخبراء الالكترونيات وعمالقة المهندسين وأصحاب الرؤى المذهلين والذين أسهموا جميعا في رسم معالم العصر الرقمي واقعاً معاشاً في يومنا هذا.

أعجبت كذلك بالرسم الزمني في بداية الكتاب والذي يوثق أهم الأحداث العلمية والمحطات الرقمية التي ساهمت في إحداث الثورة الرقمية، وبفصل الملاحظات في نهاية الكتاب، كما أن الكتاب مزود أيضا بصور فوتوغرافية حقيقية عديدة لأهم الاختراعات أو المخترعين، الأمر الذي يساعد القارئ على ربط الأحداث بالواقع المعاش آنذاك.

وعليه أنصح بقراءته، والاستفادة من الدروس الواردة فيه.

رد فعل الناس على هذه القصة.

أظهر التعليقات إخفاء التعليقاتالمكتبة متوفر في مسقط – سلطنة عمان – في مكتبة روازن – انظر الرابط التالي:

https://rawazin.om/products/%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%A8%D8%AA%D9%83%D8%B1%D9%88%D9%86

مقتطفات واقتباسات من نفس الكتاب باللغة الإنجليزية

—

The Innovators (excerpts & quotes)

By: Walter Issacson

P.172: He began to read every new patent issued. “You read everything – that’s part of the job”. Kilby said. “You accumulate all this trivia, and you hope that someday maybe a millionth of it will be useful”.

P.196: Andy Grove\’s mantra was \”Success breeds complacency. Complacency breeds failure. Only the paranoid survive.\”

P.220: “A nation which depends upon others for new basic scientific knowledge will be slow in its industrial progress and weak in its competitive position in world trade.\” -Vannevar Bush

P.276: Dozens of options for moving an on-screen cursor were being tried by researchers, including light pens, joysticks, trackballs, trackpads, tablets with styli, and even one that users were supposed to control with their knees.

P.314: For Gates, the magic of computers was not in their hardware circuits but in their software code. \”We\’re not hardware gurus, Paul,\” he repeatedly pronounced whenever Allen proposed building a machine. “What we know is software.\” Even his slightly older friend Allen, who had built shortwave radios, knew that the future belonged to the coders.

P.317: One trait that differentiated the two was focus. Allen\’s mind would fit among many ideas and passions, but Gates was a serial obsessor. “Where I was curious to study everything in sight, Bill would focus on one task at a time with total discipline,\” said Allen. “You could see it when he programmed–he\’d sit with a marker clenched in his mouth, tapping his feet and rocking, impervious to distraction.\”

P.344: Wozniak said. \”He taught me how to make an and gate and an or gate out of parts he got- parts called diodes and resistors. And he showed me how they needed a transistor in between to amplify the signal and connect the output of one gate to the input of the other. To this very moment, that is the way every single digital device on the planet works at its most basic level.\” It was a striking example of the imprint a parent can make, especially back in the days when parents knew how radios worked and could show their kids how to test the vacuum tubes and replace the one that burned out.

P.351: At 10 p.m. on Sunday, June 29, 1975, a historic milestone ocurred: Wozniak tapped a few keys on his keyboard, the signal was processed by a microprocessor, and letters appeared on the screen.

P.353: By early 1977 a few other hobbyist computer companies had bubbled up from the Homebrew and other such cauldrons… But the Apple II was the first personal computer to be simple and fully integrated, from the hardware to the software. It went on sale in June 1977 for $1,298, and within three years 100,000 of them were sold.

P.353: The Apple II also established a doctrine that would become a religious creed for Steve Jobs: his company\’s hardware was tightly integrated with its operating system software. He was a perfectionist who liked to control the user experience end to end.

P.354: For personal computers to be useful, and for practical people to justify buying them, they had to become tools rather than merely toys… Thus there arose a demand for what became known as application software, programs that could apply a personal computer\’s processing power to a specific chore.

P.358: Gates picked up the phone and called Kildall. “I’m sending some guys down,\” he said, describing what the IBM executives were seeking. \”Treat them right, they\’re important guys.\”

Kildall didn\’t. Gates later referred to it as \”the day Gary decided to go flying.\” Instead of meeting the IBM visitors, Kildall chose to pilot his private plane, as he loved to do, and keep a previously scheduled appointment in San Francisco. He left it to his wife to meet with the four dark-suited men of the IBM team in the quirky Victorian house that served as Kildall\’s company headquarters.

…Sams recalled. \”We spent the whole day in Pacific Grove debating with them and with our attorneys and her attorneys and everybody else about whether or not she could even talk to us about talking to us, and then we left.\” Kildall\’s little company had just blown its chance to become the dominant player in computer software.

P.362: Years later, at an event at Harvard, the private equity investor David Rubenstein asked Gates why he had saddled the world with the Control+ Alt+Delete startup sequence: \”Why, when I want to turn on my software and computer, do I need to have three fingers? Whose idea was that?\” Gates began to explain that IBM\’s keyboard designers had failed to provide an easy way to signal the hardware to bring up the operating system, then he stopped himself and sheepishly smiled. \”It was a mistake,\” he admitted. Hard-core coders sometimes forget that simplicity is the soul of beauty.

P.362: The IBM PC was unveiled, with a list price of $1,565, at New York\’s Waldorf Astoria in August 1981. Gates and his team were not invited to the event. \”The weirdest thing of all,\” Gates said, \”was when we asked to come to the big official launch, IBM denied us.\” In IBM\’s thinking, Microsoft was merely a vendor.

P.362: Gates got the last laugh. Thanks to the deal he made, Microsoft was able to turn the IBM PC and its clones into interchangeable commodities that would be reduced to competing on price and doomed to having tiny profit margins. In an interview appearing in the first issue of PC magazine a few months later, Gates pointed out that soon all personal computers would be using the same standardized microprocessors. \”Hardware in effect will become a lot less interesting,\” he said. \”The total job will be in the software.\”

P.363: Jobs was aroused by competition, especially when he thought it sucked. He saw himself as an enlightened Zen warrior, fighting the forces of ugliness and evil. He had Apple take out an ad in the Wall Street Journal, which he helped to write. The headline: \”Welcome, IBM. Seriously.\”

P.364: On Jobs\’s first visit, the Xerox PARC engineers, led by Adele Goldberg, who worked with Alan Kay, were reserved. They did not show Jobs much. But he threw a tantrum-\”Let\’s stop this bullshit!\” he kept shouting and finally was given, at the behest of Xerox\’s top management, a fuller show. Jobs bounced around the room as his engineers studied each pixel on the screen. \”You\’re sitting on a gold-mine,\” he shouted. \”I can\’t believe Xerox is not taking advantage of this.”

P.365: Later, when he was challenged about pilfering Xerox\’s ideas, Jobs quoted Picasso: \”Good artists copy, great artists steal.\” He added, \”And we have always been shameless about stealing great ideas.\” He also crowed that Xerox had fumbled its idea. \”They were copier-heads who had no clue about what a computer could do,\” he said of Xerox\’s management. \”They just grabbed defeat from the greatest victory in the computer industry. Xerox could have owned the entire computer industry.\”

P.399: Case applied the two lessons he had learned at Proctor & Gamble: make a product simple and launch it with free samples.

P.417: Andreessen\’s focus on continual improvement impressed Berners-Lee: \”You\’d send him a bug report and then two hours later he\’d mail you a fix.\” Years later, as a venture capitalist, Andreessen made a rule of favoring startups whose founders focused on running code and customer service rather than charts and presentations. \”The former are the ones who become the trillion-dollar companies,\” he said.

P.447: When the Mosaic browser was released, Yang turned his attention to the Web, and he and Filo began compiling by hand an ever-expanding directory of sites. It was organized by categories- such as business, education, entertainment, government- each of which had dozens of subcategories. By the end of 1994, they had renamed their guide to the Web \”Yahoo!\”

P.457: Page\’s method for reversing links was based on an audacious idea that struck him in the middle of the night when he woke up from a dream. \”I was thinking: What if we could download the whole Web, and just keep the links,\” he recalled. \”I grabbed a pen and started writing. I spent the middle of that night scribbling out the details and convincing myself it would work.\” His nocturnal burst of activity served as a lesson. \”You have to be a little silly about the goals you are going to set,\” he later told a group of Israeli students. \”There is a phrase I learned in college called, \’Having a healthy disregard for the impossible.\’ That is a really good phrase. You should try to do things that most people would not. \”

P.457: Early that summer, Page created a Web crawler that was designed to start on his home page and follow all of the links it encountered. As it darted like a spider through the Web, it would store the text of each hyperlink, the titles of the pages, and a record of where each link came from. He called the project BackRub.

P.458: As the project evolved, he and Brin conjured up more sophisticated ways to assess the value of each page, based on the number and quality of links coming into it. That\’s when it dawned on the BackRub Boys that their index of pages ranked by importance could become the foundation for a high-quality search engine. Thus was Google born. \”When a really great dream shows up,\” Page later said, \”grab it!\”

At first the revised project was called PageRank, because it ranked each page captured in the BackRub index and, not incidentally, played to Page\’s wry humor and touch of vanity. \”Yeah, I was referring to myself, unfortunately,\” he later sheepishly admitted. “I feel kind of bad about it.\”

P.460: Partly because of the huge number of pages and links involved, Page and Brin named their search engine Google, playing off googol, the term for the number 1 followed by a hundred zeros. It was a suggestion made by one of their Stanford officemates, Sean Anderson, and when they typed in Google to see if the domain name was available, it was. So Page snapped it up. \”Im not sure that we realized that we had made a spelling error,\” Brin later said. \”But googol was taken, anyway. There was this guy who\’d already registered Googol.com, and I tried to buy it from him, but he was fond of it. So we went with Google.\” It was a playful word, easy to remember, type, and turn into a verb.

P.461: The desire to turn their dissertation topic into a business made Page and Brin reluctant to publish or give formal presentations on what they had done. But their academic advisors kept pushing them to publish something, so in the spring of 1998 they produced a twenty-page paper that managed to explain the academic theories behind PageRank and Google without opening their kimono so wide that it revealed too many secrets to competitors. Titled \”The Anatomy of a Large-Scale Hypertextual Web Search Engine,\” it was delivered at a conference in Australia in April 1998.

P.463: They knew that Google was good enough to spread by word of mouth, so every penny they had went to components for the computers they were assembling themselves. \”Other Web sites took a good chunk of venture funding and spent it on advertising.\” Bechtolsheim said. \”This was the opposite approach. Build something of value and deliver a service compelling enough that people would just use it.\”

P.473: So why not make a computer that mimics the processes of the human brain? \”Eventually we\’ll be able to sequence the human genome and replicate how nature did intelligence in a carbon-based system,\” Bill Gates speculates… That won\’t be easy. It took scientists forty years to map the neurological activity of the one-millimeter-long roundworm, which has 302 neurons and 8,000 synapses. The human brain has 86 billion neurons and up to 150 trillion synapses

P.474: These latest advances may even lead to the singularity, a term that von Neumann coined and the futurist Ray Kurzweil and the science fiction writer Vernor Vinge popularized, which is sometimes used to describe the moment when computers are not only smarter than humans but also can design themselves to be even supersmarter, and will thus no longer need us mortals. Vinge says this will occur by 2030.

P.478: \”The first generation of computers were machines that counted and tabulated,\” Rometty says, harking back to IBM\’s roots in Herman Hollerith\’s punch-card tabulators used for the 1890 census.

\”The second generation involved programmable machines that used the von Neumann architecture. You had to tell them what to do.\” Beginning with Ada Lovelace, people wrote algorithms that instructed these computers, step by step, how to perform tasks. \”Because of the proliferation of data,\” Rometty adds, \”there is no choice but to have a third generation, which are systems that are not programmed, they learn.\”

P.478: In other words, is it possible that humans and machines working in partnership will be indefinitely more powerful than an artificial intelligence machine working alone?

If so, then \”man-computer symbiosis,\” as Licklider called it, will remain triumphant. Artificial intelligence need not be the holy grail of computing. The goal instead could be to find ways to optimize the collaboration between human and machine capabilities- to forge a partnership in which we let the machines do what they do best, and they let us do what we do best.

P.479: When one of the cofounders, Jack Dorsey, started taking a lot of the credit in media interviews, another cofounder. Evan Williams, a serial entrepreneur who had previously created Blogger, told him to chill out, according to Nick Bilton of the New York Times. \”But I invented Twitter,\” Dorsey said. \”No, you didn\’t invent Twitter,\” Williams replied. \”I didn\’t invent Twitter either. Neither did Biz [Stone, another cofounder]. People don\’t invent things on the Internet. They simply expand on an idea that already exists.\”

P.480: The best innovators were those who understood the trajectory of technological change and took the baton from innovators who preceded them. Steve Jobs built on the work of Alan Kay, who built on Doug Engelbart, who built on J. C. R. Licklider and Vannevar Bush.

P.485: Brilliant individuals who could not collaborate tended to fail. Shockley Semiconductor disintegrated. Similarly, collaborative groups that lacked passionate and willful visionaries also failed. After inventing the transistor, Bell Labs went adrift. So did Apple after Jobs was ousted in 1985.

P.485: Most of the successful innovators and entrepreneurs in this book had one thing in common: they were product people. They cared about, and deeply understood, the engineering and design. They were not primarily marketers or salesmen or financial types; when such folks took over companies, it was often to the detriment of sustained innovation. \”When the sales guys run the company, the product guys don\’t matter so much, and a lot of them just turn off,\” Jobs said. Larry Page felt the same: \”The best leaders are those with the deepest understanding of the engineering and product design.\”

P.485: Another lesson of the digital age is as old as Aristotle: \”Man is a social animal.\” What else could explain CB and ham radios or their successors, such as WhatsApp and Twitter? Almost every digital tool, whether designed for it or not, was commandeered by humans for a social purpose: to create communities, facilitate communication, collaborate on projects, and enable social networking.

P.486: At his last such appearance, for the iPad 2 in 2011, he stood in front of that image and declared, \”It\’s in Apple\’s DNA that technology alone is not enough- that it\’s technology married with liberal arts, married with the humanities, that yields us the result that makes our heart sing.\” That\’s what made him the most creative technology innovator of our era.